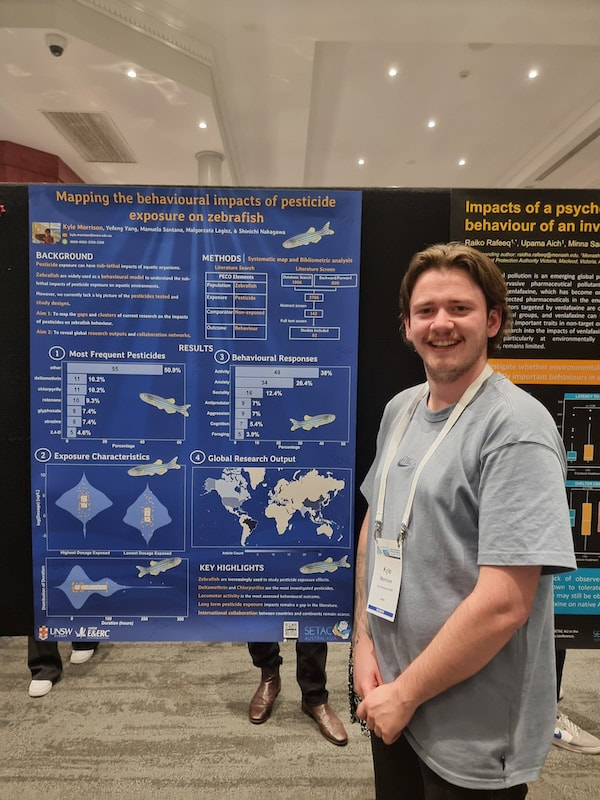

| by Lorenzo Ricolfi I've just returned from my very first SETAC-AU (Australasian Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry) 2023 Conference held in the sunny town of Townsville, Queensland, and I've got to admit, the experience was truly fantastic! Let's kick things off with the weather, which was an absolute winner – we were graced with delightful warm and dry conditions, not a single cloud in sight. And let's not forget the friendly atmosphere within the community. I was met with open arms, and I couldn't have asked for a better reception. During the event, I had the privilege of presenting my latest research on maternal PFAS transfer in wild birds. I squeezed all the good stuff into a 12-minute presentation. On the flip side, my conference companion and lab peer, Kyle, who's quite the character, got to showcase his poster detailing the quirky world of zebrafish behaviour under pesticide exposure. But, alas, Kyle's the type who always misses the good photo opportunities – he was nowhere to be found with his camera when I was up on the stage. The tables turned though, as I managed to snap a shot of him next to his poster, which was quite the victory for me. |

| Aside from all the academic jazz, we stumbled upon a rather captivating fan art exhibition right there on the beach. I know it's a tad random, but believe me, you've got to see it to believe it. And let's not forget the food at the conference – it was surprisingly good! Plus, they had an endless supply of free drinks that we tried our best, but failed miserably, to resist. After the conference wrapped up, Kyle and I decided to take a breather and treated ourselves to a glorious three-day escapade on Magnetic Island. Let me tell you, that place is a slice of paradise. I fell head over heels for every nook and cranny of it. We got up close and personal with koalas, spotted those vibrant blue-winged kookaburras, caught sight of majestic kingfishers, hung out with rock wallabies, watched kites soaring, marveled at echidnas doing their thing, and even had rays swimming by to say hello! Trust me, if you ever find yourself in northern Queensland, do yourself a favor and swing by this little piece of heaven on earth. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed