Writing is the bread and butter to all researchers. It is the main form through which our findings are communicated to the scientific community as well as to the general public – so, its important to do it well. But how does one do that? Do researchers just have a natural flair for writing?

A few weeks ago, I went to a workshop run by my supervisor, A/Prof Shinichi Nakagawa on "How to write a lot and (well)”. A/Prof Russell Boundriansky and Prof Rob Brooks were also there to contribute their tips too. Thankfully, all three academics admitted that writing is HARD, but stressed how important it is, if you want to strive in academia.

Shinichi firmly believes that there is no such thing as 'writing talent', which is very reassuring. He emphasised that through 'deliberate practice', everyone can write well. Deliberate practice in a nutshell, is about having a clear goal of what you want to improve and working towards this goal consistently with feedback and repetition. Below, I have summarised the key tips from the workshop, which form the basic ‘writer’s toolkit’ and hope this will be helpful to those that need some inspiration in their workflow. Remember - tips that work well for some, may not work well for others - but everything is worth a try!

Mindful focus

According to Shinichi, one can only deliberately practice something for no more than 4 hours. If you have trouble focussing, give Pomadoro timers a go! Do 25 minutes of completely focussed work - no emails, no distractions. Then have a 5 minute break where you can indulge in a bit of Facebook or whatever takes your fancy. Rob reckons 10 Pomadoro cycles is considered really productive day!

No reading means no writing

One of the challenges I often face is that I don't know what to write and this is usually because I haven't done enough reading. So it is crucial to read regularly and engage with the literature.

Tip 1. Shinichi showed us The Old Reader - an RSS subscriber that keeps ALL your alerts in one place. This is my new favourite thing! It keeps you updated to all the relevant journals and it also eliminates the 'Table of Contents' emails - BONUS. He recommends reading everyday, particularly influential or 'Trends' journals.

Tip 3. Find a reference manager and become a master of it. This will organise your reading. Highlight and take notes as you read. I find the functions in Papers3 very handy for this because your notes and highlights become searchable!

Tip 4. Don't like reading? Why not try an audiobook or podcast? You can listen faster than you read!

Mastery of mind maps and outlines

*You need to read enough before you can make a map

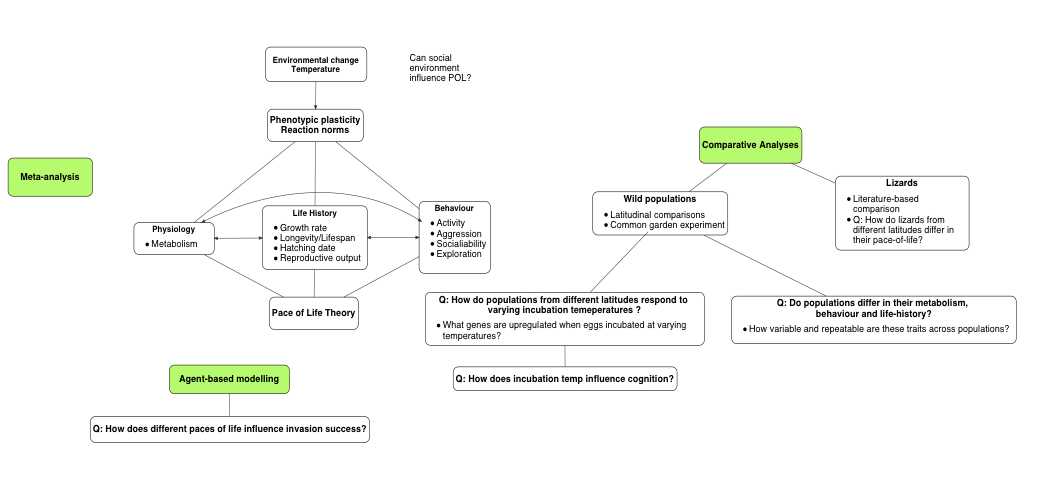

Tip 5. Put your ideas/themes/questions/hypotheses/key papers/anything on a mind map. Maps will really help you organise your thoughts and actually make you think about how ideas are linked. I use VUE, it has a simple interface and a few core functions – that’s all you need! I've also used it to make figures for presentations/papers too.

Tip 7. Transfer your notes to your outline. If some headings are low on substance, you can then go back to target your reading for those sections! EFFICIENCY!

Writing clarifies thinking

Now with your outline and notes, you can begin to write. Having your ideas chopped in sections and subsections should make workflow more manageable too, because you can work in bite-size bits. The next few tips were Russell's contribution

Tip 8. Write for a target audience. Are you targeting specialists or to the wider field? Tailor your examples and terms you use to appeal to your audience. Use this particularly in your title.

Tip 9. Keep it simple, really. Clearly written papers have the most impact. Avoid long, vague, complex sentences. Explain your idea out loud to someone out of your field and write that down.

Tip 10. Good writing is an iterative process. Re-read your writing with fresh eyes (after a week or so) and rework those paragraphs.

Tip 11. FEEDBACK FEEDBACK FEEDBACK. Ask your writing group, your lab group and supervisors. Give people enough time to review and do the same for them. Really THINK about their edits and recommendations. Don't just click 'Accept all changes'.

The work and effort that goes into writing a scientific article can be overwhelming. I really think, with the right sort of tools and habits and plenty of deliberate practice, everyone can improve and write well!

For more info on deliberate practice, check out the book: “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise” by Anders Ericsson – we are currently reading it as a lab!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed