Originally published as an online "Behind the Paper" article at https://socialsciences.nature.com/users/177900-rose-o-dea/posts/39046-slow-and-steady-our-meta-analysis-on-greater-male-variability-in-academic-performance

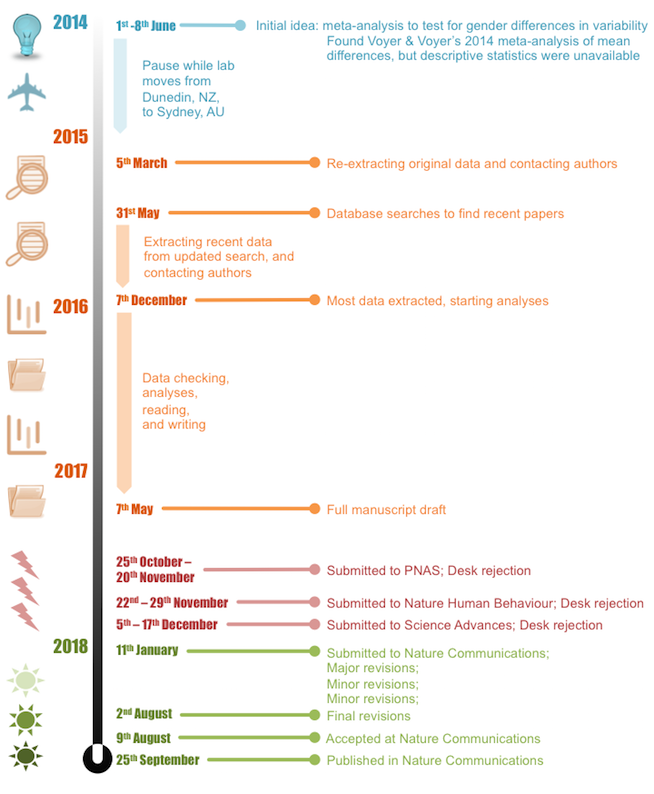

The seed for this paper was planted five years ago. Michael was sat at Losia and Shinichi’s kitchen table in Dunedin, New Zealand, listening to Shinichi describe a new meta-analysis technique he’d been developing. This technique could test for differences in variability between two groups, while controlling for differences in means. Michael suggested we use this technique to test the greater male variability hypothesis.

It would be easy. Losia found a recently published meta-analysis that tested for gender differences in average school grades; we’d do a re-analysis. It would be a simple project for Michael’s honours student, Rose, to learn some meta-analysis basics; she was joining Shinichi’s new lab in Sydney, Australia, at the beginning of 2015. The paper would be finished (we all thought) within a year, before Rose started a PhD. But it took that long just to get the data, never mind analysing and writing up our results.

But by then, this was a side-project. Not part of anyone’s grant or thesis, it was often relegated to the bottom of our priority lists. Having each other as co-authors was essential: the project never fully stagnated because there was someone else to keep it moving. Had we been doing the project alone it would probably lay abandoned.

We were also challenged by our ignorance of the field – we are evolutionary biologists and behavioural ecologists, not social scientists or psychologists. It took time to find, and read, studies that informed our introduction and discussion. Often we were missing jargon that was the key to unlocking this information. Here we are thankful to popular science communicators for bridging these gaps (e.g. the term ‘occupational segregation’, which appears in our introduction, was learnt on an episode of Freakonomics Radio), and to psychologists who commented on earlier drafts.

To make it past an editor we jazzed up our submission with a new, livelier title and abstract, and a thoughtful cover letter that sold the context of our study and asserted the confidence in our methodology. It worked – Nature Communications sent our paper out for peer review in January 2018. Extensive revisions followed (including a jazzing-down of our abstract – curious readers can read these reviewer comments and responses for themselves). With the finish line in sight this side-project became a top priority for the first time in over two years.

In the paper’s discussion we argue that being brilliant is not the key to succeeding in STEM. To make a meta-observation about our meta-analysis, this was true for our paper. We took a seemingly simple idea conceived around a kitchen table and, while it grew into a much larger, harder, and more time consuming paper than we’d expected, we supported each other and we persisted.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed