To Sydney for the whales (well, that was at least one of the reasons)

In 2016, I moved to Sydney to start my PhD at the University of New South Wales. My PhD investigated the airway bacteria in whales and dolphins. Sydney is the perfect place to study whales as every year between June and October thousands of majestic humpback whales roam its coastal waters migrating to and from their breeding grounds. I have always been fascinated by whales and the elegant way they move in the water. The whales and I certainly share the excitement for their fluid habitat.

The dark side of whale research

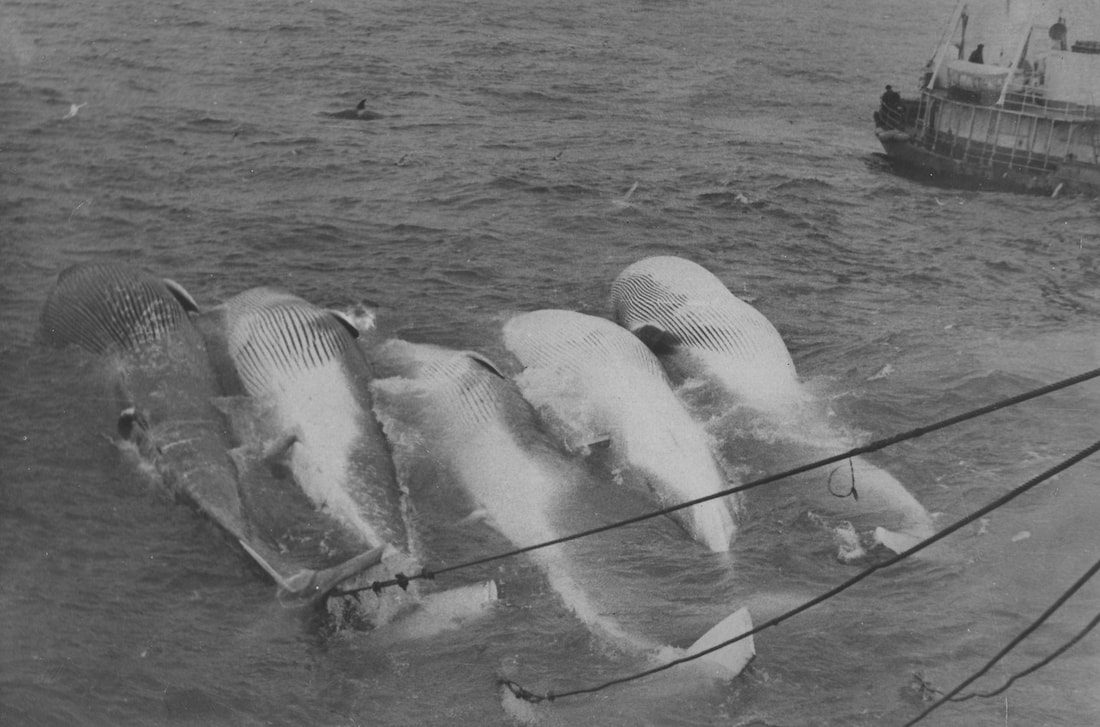

I was quite curious to learn that the population of currently around 30,000 humpback whales passing by Sydney every year was once severely depleted. In the 1970s and 1980s only a few hundred individuals remained. The culprit was easy to spot as the industrial whaling fleets of the 20th century were infamous. However, the more I learned about the issue the more intrigued I became. It wasn’t ‘just whaling’ that almost wiped out the entire population of east Australian humpback whales. What happened there was a brutal yet surprising event in modern history that a world-leading whale expert once called ‘one of the greatest environmental crimes of the 20th century’. The culprits are long dead, but the memory of their crimes lives on.

The text below was originally published in German in Wissenschaft' (Springer Nature, German version of Scientific American). The photos are reproduced with permission from their current owner.

Japan, Norway and Iceland are the countries we usually associate with whaling. But are they really to blame for the massive decline of whale populations in the 20th century? The truth is much more complicated and includes a secret that was kept for almost 50 years.

The waters surrounding Australia and New Zealand once had thousands of migrating humpback whales. In 1961 this picture changed and all of a sudden the Southern Ocean resembled a vast aquatic desert. The shore whaling stations in NZ and Australia closed down, as most of the whales were gone. Almost 26,000 humpback whales had disappeared within 2 years and at the time the reason was unknown.

The secret was revealed only in 1993 and it became public knowledge who the actual perpetrator was. In only 30 years of intensive whaling (about 1948 to 1975) the Soviet Union (USSR) had not only almost destroyed the humpback whale population around NZ and Australia, but had caught about 370,000 whales in total, mainly in the Southern Ocean. At least 180,000 of those catches were illegal.

The USSR entered industrial whaling on a large scale comparably late in 1946, when most whaling nations had already been part of the business for decades. In the same year, 15 countries came together to create the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) and the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The treaty they all signed (including the USSR), was to end the reckless whaling strategies that had significantly depleted whale populations world-wide. The purpose was not whale conservation as such, but turning commercial whaling into a sustainable industry. The treaty determined catch quotas, introduced minimum sizes for captured animals and completely banned whaling for a few particularly endangered species like the right whale.

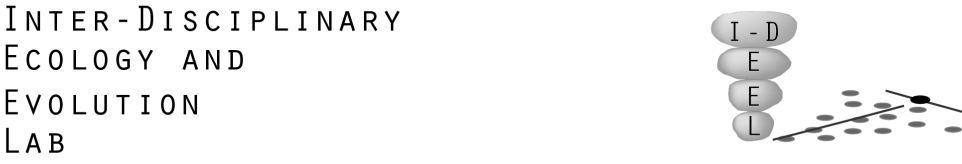

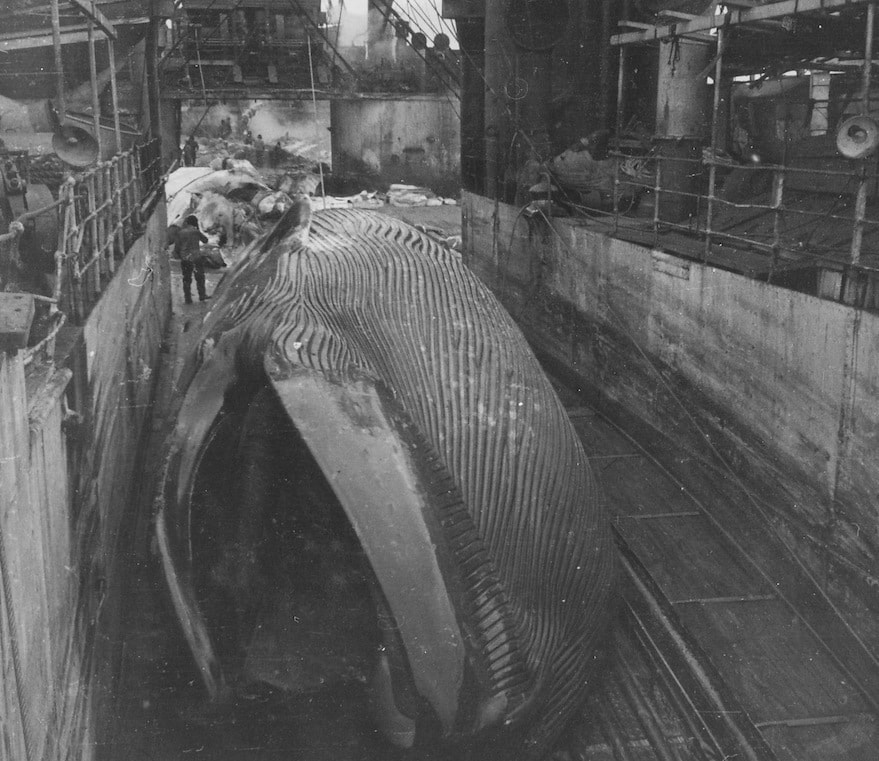

As it turned out, the USSR had little intention to stick to the treaty. Every season the country sent out up to 5 whaling fleets with a large factory ship at its heart. Each populated by up to about 600 crew members, the ships were like floating cities. The processing on board was highly efficient: A whale was taken to pieces within 30 min. Up to 25 smaller catchers and scout boats accompanied each factory ship. What happened to the whale depended on its species: Toothed whales, predominantly sperm whales, were turned into industrial oil and animal food. Only the meat of baleen whales, like blue and humpback whales, was used for human consumption. Their oil provided the base for margarine. A large percentage of all whale carcasses were turned into bone meal and used as fertilizer.

The number of whales killed increased every year. Catcher boats regularly caught more whales than the factory ships could process. Hence the carcasses started rotting while floating behind the catchers. As a result the flensers often stripped off only the blubber of the carcasses and threw the remains back into the ocean.

Why did the USSR kill so many whales, even though the country had comparatively little use for their products?

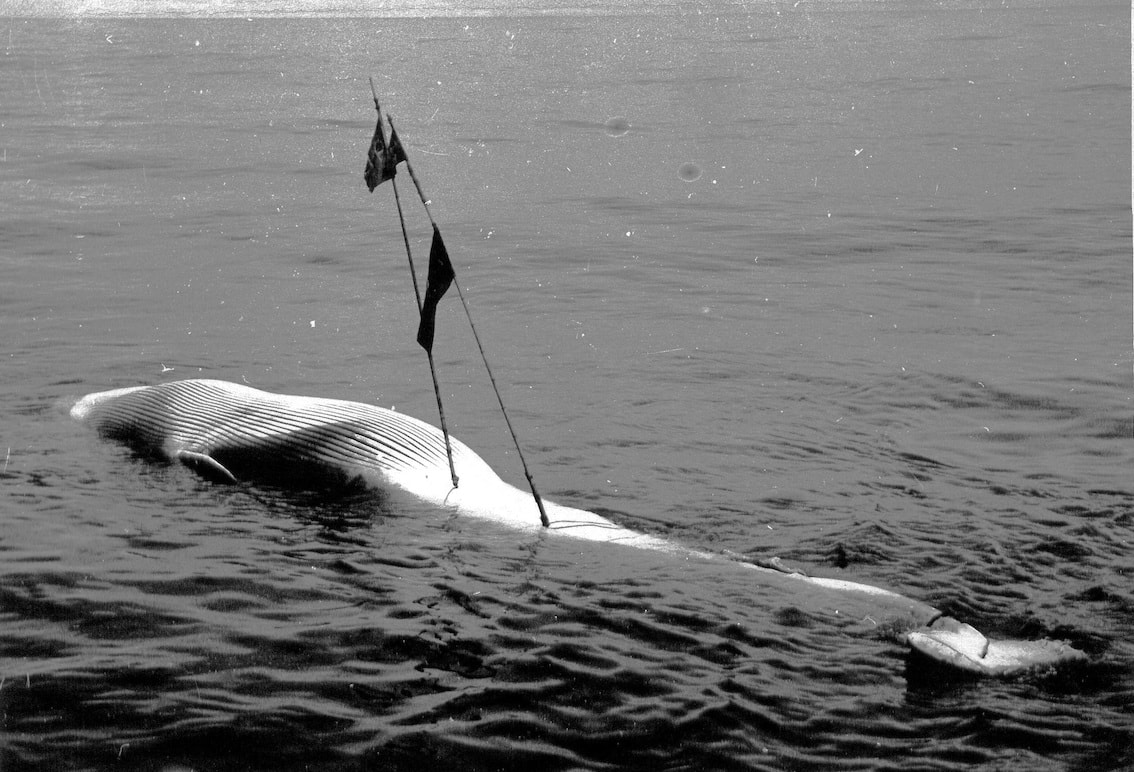

The devil lies in the detail of the economic system of the USSR. Being a worker in the Soviet whaling fleet came with many privileges: Salaries were among the highest paid in any industry, due mainly to large performance bonuses. Before the start of every whaling season, the government set monthly and yearly production targets (as they did for every Soviet industry). In whaling this determined the number of whales to be caught. Production targets had to be met. If targets were not met, everyone involved expected punishment. Supervisors reported on the performance of their subordinates and if output was low, employees lost their jobs. On the other hand, if the fleets met or even exceeded the target, the government rewarded employees with generous bonuses. Motivation to meet or even exceed the production target was naturally high. The production output of the previous whaling season often set the target for the upcoming year. Yearly targets inevitably kept increasing at a greater rate. In addition, workers in the whaling industry were well-regarded in the public eye with large celebrations at their home port on their return to the USSR. Newspapers honoured the whaling crews like heroes.

Soviet whaling was a highly subsidized industry and it quickly developed into a massive financial loss for the country. As with any other industry in the USSR, whaling was not primarily meant to provide communal profit but to show proof of the efficiency and superiority of the communist system. In the case of whaling, proof was provided by being able to kill more whales than any other nation in a relatively short time.

In theory, catching numbers were in accordance with the conservation status of the targeted whale populations. Almost every factory ship had scientists on board who conducted research on the whales. The scientists regularly submitted recommendations on sustainable yields to government authorities. Most of the time, their advice was ignored. A group of Soviet biologists while well aware that any opposition to the status quo would severely impact their careers, repeatedly criticised the country's whaling practices in the 1960s. One was were eventually summoned to the Minister of Fisheries in Moscow. The biologist stated that if whaling continued at the current rate there wouldn’t be any whales left for their his grandchildren. The Minister of Fisheries responded to these objections by stating that ‘Your grandchildren aren’t the ones who can remove me from my job!’

To avoid being sanctioned for breaking international law, the USSR submitted reports with falsified data to the International Whaling Commission for more than 3 decades. The true dataset was considered highly classified. Ultimately, in 1993 the Russian whale biologist, Alexey Yablokov, who had worked for the whaling industry was the first to break the silence and set off an avalanche of publications about the true nature of Soviet whaling.

The commercial whaling activities of countries like England, Denmark, Norway, USA, Japan, South Africa and Chile had already significantly depleted the majority of world-wide whale populations, before the Soviet Union started its massive whaling campaign in the late 1940s. However, the whaling activities of the USSR caused a downward spiral of many populations to the point where the Southern Ocean humpback whales and the North Pacific right whales were almost extinct. The humpback whales were lucky. They have recovered remarkably over the past decades. Their numbers are believed to have almost reached pre-whaling status. However, the North Pacific right whale is currently facing a different fate. Only a few dozens of individuals are left in the eastern North Pacific population, and they may well never recover. Dr Phillip Clapham, a world's leading expert on large whales, called the illegal whaling activities of the USSR ‘one of the greatest environmental crimes of the 20th century’.

References:

Clapham, P. and Ivashchenko, Y., 2009. A whale of a deception. Marine Fisheries Review, 71, pp.44-52.

Clapham, P., Mikhalev, Y., Franklin, W., Paton, D., Baker, C.S., Ivashchenko, Y.V. and Brownell Jr, R.L., 2009. Catches of humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, by the Soviet Union and other nations in the Southern Ocean, 1947–1973.

Ivashchenko, Y.V., Clapham, P.J. and Brownell Jr, R.L., 2011. Soviet illegal whaling: the devil and the details. Marine Fisheries Review, 73, pp.1-19.

Ivashchenko, Y.V. and Clapham, P.J., 2014. Too much is never enough: the cautionary tale of Soviet illegal whaling. Marine Fisheries Review, 76, pp.1-22.

Rocha, R.C., Clapham, P.J. and Ivashchenko, Y.V., 2014. Emptying the oceans: a summary of industrial whaling catches in the 20th century. Marine Fisheries Review, 76, pp.37-48.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed